Let’s start by first taking a look at some fundamental principles of pricing.

The first principle: Costs do not determine the price

Price has everything to do with how much your customers are willing to pay. In other words, your costs don’t drive your pricing – your customers do.

Sure, costs play a role. They determine whether it’s feasible to build the product you want. If the price customers are willing to pay is less than the cost of building and selling the product, it obviously isn’t feasible to proceed. But beyond that, costs have little to do with pricing.

The second principle: Humans can’t infer prices

We humans find it tough to look at something and determine its value. For example, check out the car in this picture.

Unless you have a ton of background knowledge on cars, you have no way of pinpointing its current value. It could be US$ 2,000, US$ 20,000, US$ 2 million – who knows? Without some additional information, you can’t know for sure.

The additional information we use to figure out a product’s value sometimes is the pricing of other products.

The third principle: Price implies quality

Before buying, customers assess the quality of a product in different ways. For example, social proof like recommendations from friends, G2 ratings, testimonials, and so on.

Customers also use other “proxies” to figure out the product’s relative value. For example, its design and aesthetics. If a product looks great on the outside, it’s easy to imagine that it looks and works great on the inside.

That’s why a luxury car seems to have higher quality, even if its actual functionality might be the same as a cheaper car. The same goes for a haircut: getting a trim at a basic chain salon feels different from a high-end salon with all the bells and whistles.

The other proxy customers often use to judge quality is the price.

Higher price doesn’t actually mean better quality – it simply implies it.

This perceived increase in quality also boosts sales, up to a point.

Let’s take a look at the relationship between pricing and quality perception.

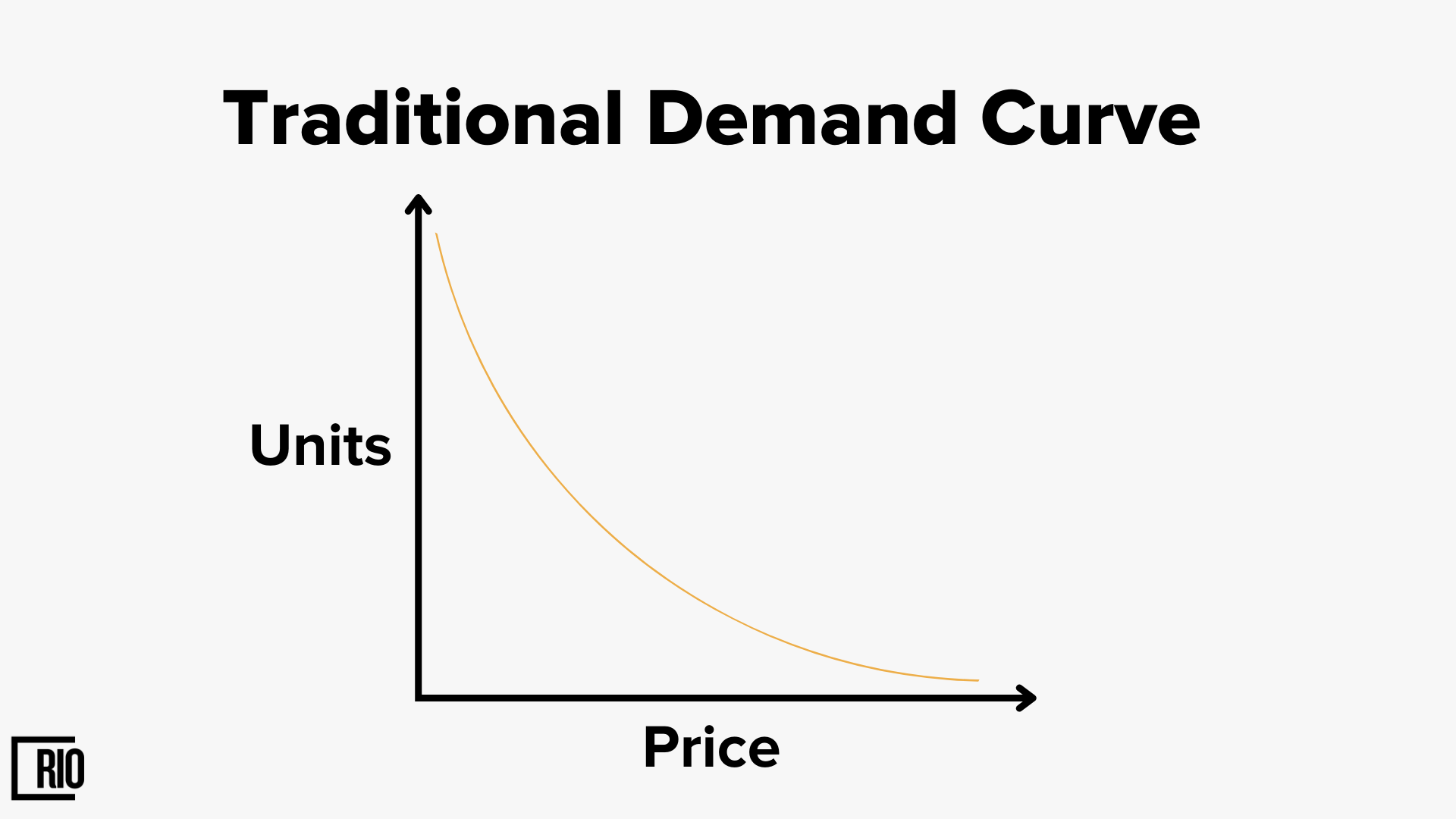

It’s generally thought that demand follows a simple path: as price increases, sales decrease. The logic here is that the cheaper a product is, the more people will buy it. The more expensive it is, the fewer people will buy it.

As it turns out, the idea behind this generally accepted demand curve is wrong when it comes to non-commodity products.

In 2010, Professor Min Ding of Pennsylvania State University published research in the Journal of Retailing which showed that price is an indicator of quality – and that the indicator of quality can increase sales. (By the way, this paper won the 2012 Davidson Best Paper Award.)

Professor Ding conducted tests in which the same product was presented at different price points to see what effect price had on sales. Over and over again, he found that price was seen as a sign of quality, and up to a point, higher prices actually increased sales.

Based on these findings, Professor Min Ding concluded that the demand curve looks more like this.

In this curve, you can see that at a very low price, often free, a large number of products are sold. People like free things.

At a slightly higher price, sales drop pretty drastically.

However, at an even higher price point, sales actually begin to increase.

Of course, there’s always a limit. At some point, the price becomes too high and sales start to dip again.

Look at that “bump” in the middle. Your aim should be to identify at what price that bump is highest, so you not only maximize sales but also total revenue.

Unfortunately, almost all early-stage founders undercharge for their products. The fear of losing customers because of a too high price point is so great that they end up underpricing their products.

By pricing your product too low, you’re making a statement about the quality of your product. You’re saying your solution is of bad quality. And this will ultimately mean you’ll sell less, not more.

Instead of fear, you need to use logic while deciding on the price of your product.

That’s why I’m a huge advocate of value-based pricing. That means you define your pricing based on the value you provide to your customer.

Value-Based Pricing & Anchoring

What does your product help your customer with? Does it save them time and/or money? Does it help them make more money? Does it reduce risk? Does it make it simpler for them to comply with regulations?

Always try to put a cash amount on the value a customer gets by using your product. Value-based pricing has two main benefits:

- You can potentially begin at a higher price point if you can show a higher value-add and willingness to pay among your customers.

- You can raise your prices as you find out more about your customers and add features to your product that provide greater value.

If you know what value your product provides and how your target customers measure it, you also have a good hypothesis for what your product is worth to them. So, at least in the B2B scenario, you can figure out the answers to these questions with some certainty:

- Is your solution making them money? If yes, how much?

- Is your solution saving them money? If yes, how much?

- Is your solution related to compliance? What is the average cost per year if they don’t comply?

A good rule of thumb is that you can charge at least 10-20 percent (if not more) of the value your customer is receiving thanks to your product. This is a logical starting point for your pricing. Not only is it justifiable but will also probably be perceived as fair by the customer.

Once you’re clear about value-based pricing, you can move on to addressing external factors like competition and substitute products.

Start by analyzing the pricing in the market and among your competitors. Invest some time into listing and assessing the packages and pricing offered by your competition.

Don’t forget to check out substitute products that can solve your customer’s problem in a very different way. For example, the biggest competitor for a business class seat in an airline isn’t another airline but a good quality web-conferencing system.

Since people can’t infer prices, they use comparison to analyze whether an item is too expensive or too cheap. This “anchoring” happens in different ways:

- What is the cost of not buying a product?

- What are the substitute products and the value they provide? Substitute products are your indirect competitors.

- What have they paid in the past for similar products?

- What are the value and pricing of similar solutions? What about your direct competitor?

- What is the original value vs. discounted price? You may have noticed that in supermarkets, some items seem to be permanently on discount. That means they’re trying to anchor a higher price.

Your first priority is to anchor your price in the value your product delivers, i.e. a percentage of time saved, or money saved/made thanks to your solution. What percentage to take, however, is often not clear. While 10-20 percent is a good rule of thumb, it doesn’t apply in each and every situation.

In such a case, anchors from the outside market can help you reach the highest justifiable price.

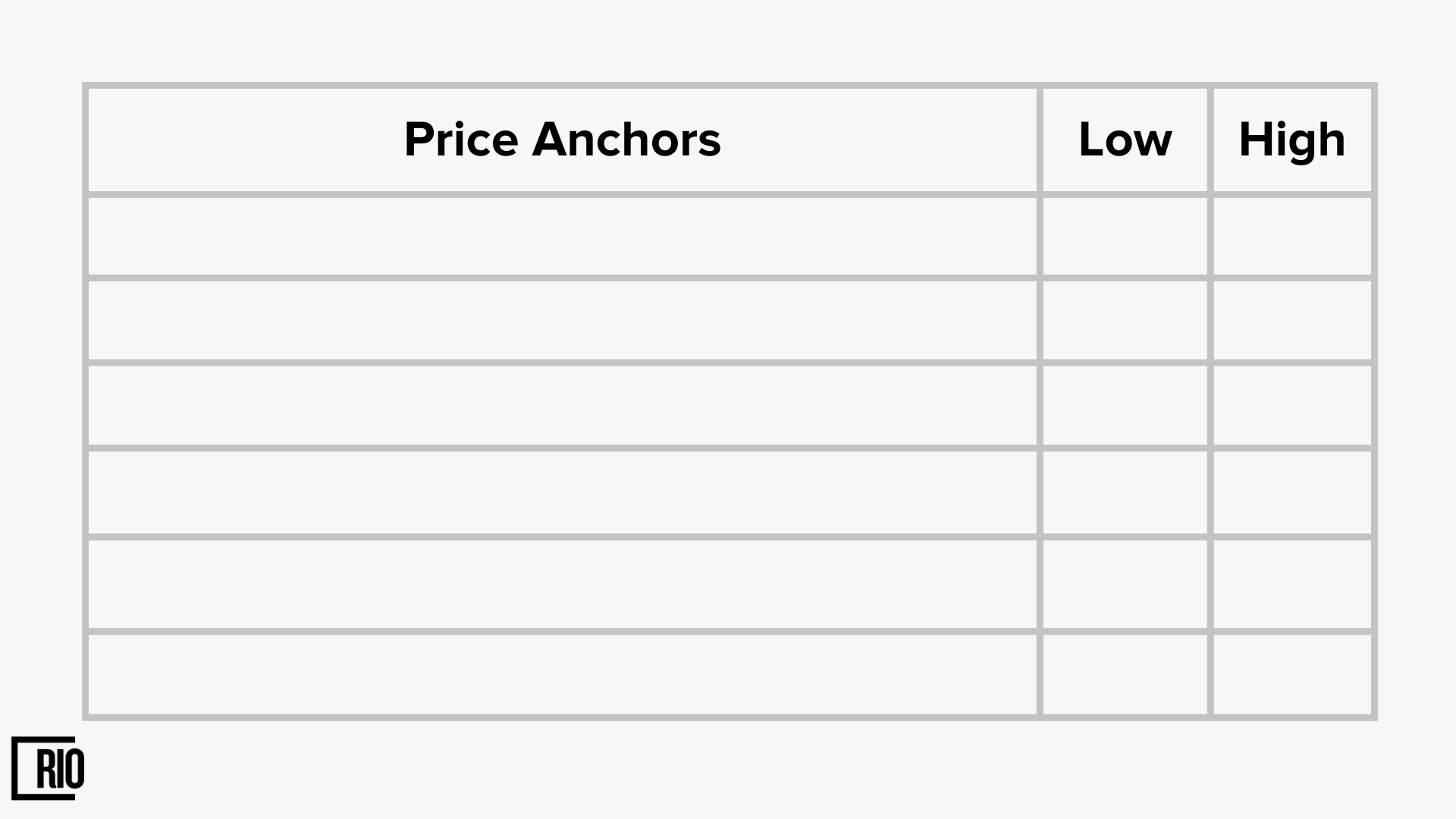

Use the table below to list all the anchors your customer could take as a reference when thinking about the value vs. pricing of your offer. Mention low-end and high-end pricing for each anchor.

Then, take the anchors that are most comparable with your solution. From among these, take a reference price between the highest-priced anchor and the high value of the lowest-priced anchor. This should give you a good point of reference for determining your own product’s price.

Remember, you don’t want your solution to be seen among the cheapest options – unless being cheaper than everybody else is your UVP.

As you begin with one target segment of customers, start with one pricing plan until you achieve the product-market fit for this segment.

In the next round of product-market fit, as you expand to another target segment, you’ll go through the whole process again and create another pricing plan tailored to the new segment.

Happy Selling!